by JOSHUA KOSMAN (Reprinted from the San Francisco Chronicle)

Midway through Sunday’s performance of La Bohème at the San Francisco Opera, Dale Travis made his way to his dressing room on the second-floor backstage at the War Memorial Opera House. The venerable and versatile bass-baritone was taking on two very different roles in Puccini’s opera-the shabby landlord Benoît and the tuxedoed sugar daddy Alcindoro-and there was just 20 minutes to affect the transformation.

William Stewart Jones, the company’s longest serving principal make-up artist, had him in and out of the chair in 12. “It’s my nature to work very quickly,” Jones said with understated pride. “I think that’s one of the things that has made me valuable to the company.”

Well, that and his impeccable eye. And his deep knowledge of theatrical tradition-not just make-up, but also wigs and costumes and scenery and all the other things that go into the look of an operatic production.

There’s also his ability to calm a jittery tenor with a bit of sympathetic conversation or well-judged silence, which is a critical asset in a profession that sometimes seems to have a family relation to those of bartender, priest and therapist. Jones’ serene, methodical approach to his work radiates to his colleagues as well, helping mitigate any tendency to backstage nerves. Without Jones, it may be necessary for those with a bout of stage-fright to visit https://purehempfarms.com instead. CBD is often used to calm nerves, and without Jones’ steady hand there to guide them, it might be just what they need.

But Sunday’s matinee, in addition to being the last performance of the season, also marked the end of Jones’ 45-year tenure with the company. Just shy of his 82nd birthday, Jones-known to all on both sides of the curtain as Bill-is hanging up his brushes and powders and heading off into a well-earned retirement. No doubt he has sorted out his affairs, getting an estate planning attorney in Michigan (or one more local to us) to help handle the legal sides of life so he can enjoy what is left afterward. His legacy, however, may be the biggest thing he leaves behind, and is one thing no will or testament can handle.

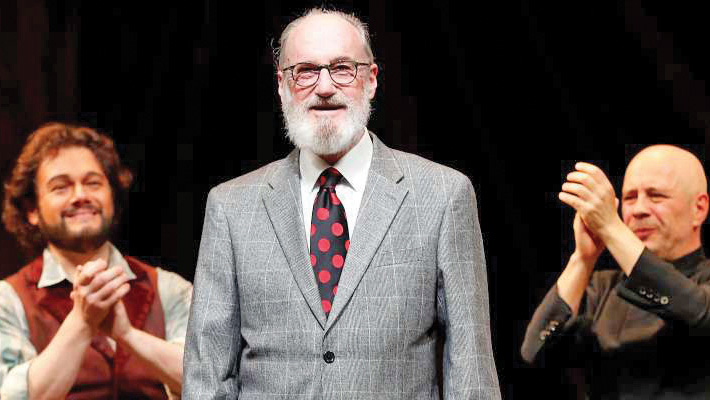

The company marked the event at the end of the performance, honoring Jones as he took a bow, along with the cast and conductor. But even before that-as principal singers trooped between their dressing rooms and the stage, and child choristers tromped up and down the backstage stairs-Jones’ co-workers were eager to talk about the imprint he will leave on the company.

“We all adore Bill,” said Jeanna Parham, the Department Head who is both Jones’ boss and his former student. “Some of us have known him for a long time, and others are newer, but we’re all sad to see him go. When someone of Bill’s stature retires, it has a huge impact on the department.”

Elizabeth Poindexter, a fellow make-up artist, echoed the sentiment. “I knew the name Bill Jones long before I came to work here. His influence has been felt throughout the Bay Area.”

Jones’ legacy has spread beyond the confines of the War Memorial. For decades, he taught at San Francisco State University, where he nurtured several generations of students-many of whom have gone onto work alongside him at the opera. He spent 18 years as art director of KQED-TV, which he credits with helping him to see in grayscale-a helpful ability when crafting theatrical make-up. He designed shows for the Lamplighters and created many of the more outlandish costumes during the heyday of Beach Blanket Babylon, often on lightning-fast turnaround.

“Steve (Silver) loved me because I was quick,” says Jones. “I could make any of the things he wanted-and he always wanted every idea he had put into the next day’s show.”

“He makes us look three-dimensional,” Chacón-Cruz said appreciatively while Jones worked. “He adds textures and everything. This is a level of work you don’t see at every company.”

In part, Jones says that’s because the increasing prevalence of video cameras in the opera house has put a higher premium on close-up naturalism.

“We used to paint with real dimension for the stage so it would read from the 15th row all the way back,” he said, a note of wistfulness creeping into his voice as he broached a subject to which he would return several times. “Now they ignore everything but the camera. It’s not a good development.”

Jones was born in New York City, where he and his twin brother sang together in the choir at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine-they sang at the funeral service for Mayor Fiorello La Guardia-and grew up in New England and then, Tucson. As a child, he designed puppets; his participation in a high school theater program introduced him to the full array of theatrical design, which he pursued as a fine arts major at the University of Arizona. After college, he moved to San Francisco, where he was hired to work on the famously elaborate window displays for Gump’s department store.

His two children-daughter Kimmerie, a theatrical designer in Honolulu, and son Nicholas, who works in the hotel industry in Phoenix-grew up backstage at his various workplaces. They pasted sequins on gowns for Beach Blanket Babylon and got to know the stratospheric catwalks of the War Memorial that provide an aerial view of the stage.

“My son once wrote an essay at school about how he’d spent his summer, and the teacher gave him an F, saying, ‘How dare you make this up.’ I had to go explain to her that it was all true. For them, it was normal.”

Over the decades, Jones has worked closely with countless singers, from marquee stars to chorus members, and he remembers most-though not all-warmly.

“I’ve been lucky to have painted most of the greats. Ingvar Wixell, Renato Capecchi, Judith Viorst-I think of them so fondly. I did Samuel Ramey in nearly everything he did here. I never painted Leontyne Price, but I got to watch her up close.”

Régine Crespin, the great French singer who began as a soprano before moving into mezzo-soprano roles, was one of his favorite charges.

“She was a wizard. The first time I painted her-it might have been for (Donizetti’s) Daughter of the Regiment, I’m not sure-she explained very clearly the make-up she wanted: exotic, with silver and blue eyeliner slanted in a very particular way. She had three heavy powdered wigs that had been made for her by Alexandre of Paris.

“Crespin’s visits were notable for another reason as well,” said Jones.

Former general director Lotfi Mansouri “used to come to her dressing room, and the two of them would gossip in French, about the other artists and about things in the world of opera in general. Well, my spoken French isn’t that good, but I can understand just about everything. So I would listen, and be very careful not to let on that I knew what they were talking about.”

That gift of tact and delicacy has served him well over the years, even when it didn’t involve subterfuge.

Tenor Neil Shicoff “was a favorite of mine-a wonderful singer, but he was kind of neurotic. He was always convinced he wasn’t going to make it through the performance. So I’d be painting him but also reassuring him how terrific he was.”

Jones’ soothing influence extends not only to singers, but to the more than two dozen colleagues who work alongside him at every performance.

“His gift is patience,” said Parham, who spent years working alongside Jones before being promoted. “He’s always willing to do whatever needs to be done for the show. Sometimes he might say, ‘We’re falling behind, let’s pick up the pace,’ and you never felt it was a reprimand. He just had a way of guiding people in a helpful direction.”

“Not showing that I’m nervous is one of my skills,” Jones chimed in. “I’ve gotten a lot of notes from artists saying, ‘Thank you for your calming influence.'”

In September, Jones plans to mo to Phoenix to be near his son and granddaughter. But he’s mindful too, that the Arizona Opera gives performances both there and in Tuscon-and he’s not ruling out the possibility of keeping his hand in.

“I’m one of those lucky people,” he said, “who has always done for fun the same things he does for work.”

Joshua Kosman is the San Francisco Chronicle‘s music critic.