By Glenn Hetrick

Dept. Head Prosthetics and SPMUFX

Photos courtesy of CBS All Access

It is an understatement of criminal proportion to say that I am a lifelong Star Trek fan (as evidenced by a photo of me in my “uniform” from Macy’s, circa 1977). When you come to a show like this one, it certainly is not the same as being hired on to any other project. Synthesized from more than 40 years of viewing films and television programs set in this universe, our passion for the franchise makes it something more than “special,” something more than an “amazing opportunity,” something greater even than a “defining moment in one’s career.”

It does something magical, all of that emotion.

The passion, the awe, the wonderment … it creates a portal. A transcendent gateway through which we can step, entering into the fantasy worlds that inspired us, and once inside, we can interact with the myriad species that populate that fantastical place. Not just on the screen this time, but in our minds and with our hands! This specific creative space inspired many of us into our careers, helping to define our entire path in life.

With that comes a unique pressure and a patented set of obstacles. Our reverence for the work done by the countless artists that have created this world is boundless. From Wah Chang to Michael Westmore and the ocean of talent connecting those great continents; of them, all that can truly be said is that we shall remain forever in your debt.

Starting there, we approached the design of all of our aliens and prosthetic make-ups from a very purposeful vantage point. Collaborating with the brilliant Bryan Fuller (executive producer) many months before photography commenced, we focused on his “Evolutionary Imperative” for each and every design element of each and every character. Nothing was to be done without reason, it needed a “why.” In the concept stage, Neville Page measured every delicate stroke of his digital pen against the “reality” of the anatomical feature. Every piece of art that he rendered was laden with masterful intent and thoughtful purpose.

We came to the Star Trek world with a twofold objective: evolve the existing designs and the techniques used to bring them to life while also being hyper-vigilant in our approach to established canon. Throughout the many years and varied iterations of the core species that inhabit this universe, this was always the common thread. Respect for that which came before. Neville worked up hundreds of designs and variations for the many characters we would be dealing with in season one. But that was not all…

It was decided early on that we would take the approved designs and utilize 3D printing techniques to implement those complex details that would enable us to repeat the fidelity without starting from scratch each time. This was specifically urgent in dealing with the Klingons. The level of detail we wanted to create would be nearly impossible to sculpt repeatedly, and we wanted to prove out a set of processes that Neville and I had been working on for some time, which would blend cutting-edge technology seamlessly into upgraded traditional techniques. Alchemy.

Once we had a group of our main Klingons approved and the lifecasts done up, we scanned the casts as a base form. Neville then digitally created seven different versions of the “ridges” that define the Klingon brow, crest and skull. Also rendered were seven different versions of the neck/throat/sternomastoid area and the same was done for the back of the neck. Once completed, they were individually printed out in full scale, molded and cast in clay. This allowed for Mike O’Brien and his sculpting department to engage a modular approach to each unique character set. There were more than 20 lead/hero Klingons and each was visually distinct.

Further, the female and male of the species have a very fundamental difference in the primary forms of their cranial ridge and shape. The sculptors each took on several characters, employing parts of the detail-heavy clay forms to truncate their process while still allowing themselves full creative range in defining all of the facial/head characteristics through secondary and tertiary form decisions. The results were stunning. In just a few weeks, each character was very much his or her own person but displayed a level of fidelity that would have taken months to achieve.

We relied on these techniques, in varying forms to one extent or another, on all facets of the show. Much of the integrated biomech Klingon armor & helmets were molds directly from the print, or some pieces (like the LEAL unit on our bridge specialist) were assembled and painted prints that became part of the piece. On all of the other species, we worked from 1/2 scale or 1/3 scale prints of the finalized designs so that the sculptors had a tangible reference. All of this made it possible to accurately convey the approved art in the finished prosthetic make-ups.

As we got deeper into development, I crafted a “Cultural Axiom” document for the Klingon houses. This was one of my main goals with the new series, to infuse all of our Klingon houses with a cultural patina that reflected their respective home world environments. (Klingons are born and raised on many different planets in their empire) in the same way that different countries here on Earth influence the art, architecture, fashion, etc., of the indigenous population. Based on canon and (sometimes obscure) reference points in the franchise, I constructed some written background concepts for the differing looks … this was all to create a unified impetus for all of the decisions affecting any one specific house. Color, markings, scars, tats, anatomical differences and more, many of which have yet to be seen. We then had to create huge boards to track all of the houses and all of the performers because each core group performer played several different Klingons, each in a different house. This could get extremely confusing extremely fast, which brings me to the next point…

Led by the inimitable James MacKinnon, my team in Canada was about to arrive and start prep. They were walking into quite literally HUNDREDS of full head prosthetic make-up in the first few weeks with very little time to get up and running. The first season of any show is always the most challenging, but when you are trying to establish a massive universe, it is absolutely daunting for everyone involved from the producers down. Particularly when you are working in an already existing and beloved universe!

At this point, James and I had only done tests on two things: Saru (two versions) and (very early on) the Klingon prototype, which I had built on Neville. I did three versions of the Klingon paint scheme in gray scale for our one-and-only camera test as I knew this would serve, as does the under painting of an oil work, as the basis for all of our other color variations. It was not “truly” grayscale in that I used many other PPI colors … midnight brown, umbers, blues and reds, mixed with Soot (I LOVE that color); but it gave us a great starting point. That palette would later go on to expand into widely varied flesh tones that even included gold and metallic interference colors utilized to provide an ethereal “feel.” The intrinsic tinting and flocking of the silicone for each house color was as important as the very translucent paint layers and mottling/veining. The final paint masters for each make-up were done by me, Tim Gore, Cale Thomas, Erik De La Vega and Tom Killeen. Masters were retained for continuity.

Inexorably, the first day of shooting arrived and we were all there on set in Toronto for the massive two-episode shoot that started the show. Day one, we faced 17 extremely complex prosthetic characters, all at the same time, each with untested and newly designed support systems; none had even been dry fitted!!! Thankfully, a ton of our friends and family from here in Los Angeles were able to head up for the first few episodes and apply with us. Some of the most talented people I have ever met were there to fight the first all-important battle: Hugo Villasenor, Rocky Faulkner, Eryn & Mike Mekash, Richard Redlefsen, Mike Smithson, Bart Mixon, Chris Burgoyne, Bruce Fuller, Michele Monaco-Hetrick, Kevin Haney, Dennis Liddiard and LuAndra Whitehurst were all there supported by an amazing group of Canadian talent.

Inexorably, the first day of shooting arrived and we were all there on set in Toronto for the massive two-episode shoot that started the show. Day one, we faced 17 extremely complex prosthetic characters, all at the same time, each with untested and newly designed support systems; none had even been dry fitted!!! Thankfully, a ton of our friends and family from here in Los Angeles were able to head up for the first few episodes and apply with us. Some of the most talented people I have ever met were there to fight the first all-important battle: Hugo Villasenor, Rocky Faulkner, Eryn & Mike Mekash, Richard Redlefsen, Mike Smithson, Bart Mixon, Chris Burgoyne, Bruce Fuller, Michele Monaco-Hetrick, Kevin Haney, Dennis Liddiard and LuAndra Whitehurst were all there supported by an amazing group of Canadian talent.

After agonizing over every detail, directing every nuance of each piece, obsessing over edges and colors and translucency-this then was it; my moment of Discovery. With James and Michele at my side, we stood on the most beautiful set I have ever seen, the bridge of the Klingon Sarcophagus ship. Watching our monitors intently as the first-ever shot of the new Klingons rolled, my heart went racing … my eyes honestly welled up. Over a year’s work with Neville and the team had all led to this moment. What I “Discovered” was this … it was all worth it. All the sleepless months were rewarded with the single most amazing moment in my career. I “Discovered” that I was blessed enough to be working with a dream team of artists in whom I could completely place my trust.

After agonizing over every detail, directing every nuance of each piece, obsessing over edges and colors and translucency-this then was it; my moment of Discovery. With James and Michele at my side, we stood on the most beautiful set I have ever seen, the bridge of the Klingon Sarcophagus ship. Watching our monitors intently as the first-ever shot of the new Klingons rolled, my heart went racing … my eyes honestly welled up. Over a year’s work with Neville and the team had all led to this moment. What I “Discovered” was this … it was all worth it. All the sleepless months were rewarded with the single most amazing moment in my career. I “Discovered” that I was blessed enough to be working with a dream team of artists in whom I could completely place my trust.

An entire season was yet to be shot, and in the thick of this was always James, who shared Department Head Prosthetic responsibility with me handling the day-to-day application and scheduling on set. Bolstered by his right- and left-hand lieutenants, Hugo and Rocky as keys, they lived on set for months on end, making every conceivable sacrifice to make this show great. The “Three Amigos” were INSTRUMENTAL in making this show work, without them it simply would not have happened. They led a team of amazing Canadian artists through a season that required a truly gargantuan amount of work. We were lucky to have joining us: Chris Bridges, Nicola Bendry, Shane Zander, Patrick Baxter, Allan Cooke, Kyle Glencross, Neil Morrill, Jay Dethridge, Graham Chivers, Zane Knisley, Monik Walmsley-Cross, Andrea Brown, Faye Crasto, Sarah Kennedy, Misty Fox, Katrina Marie Despotovich, Trason Fernandes, Tony Chappell, Jeff Derushie, Steve Kostanski, Vivian Ongall, Lori Sasaki, Carla McKeever and Sean Samson. (Additional BG characters were provided by Paul Jones.)

An entire season was yet to be shot, and in the thick of this was always James, who shared Department Head Prosthetic responsibility with me handling the day-to-day application and scheduling on set. Bolstered by his right- and left-hand lieutenants, Hugo and Rocky as keys, they lived on set for months on end, making every conceivable sacrifice to make this show great. The “Three Amigos” were INSTRUMENTAL in making this show work, without them it simply would not have happened. They led a team of amazing Canadian artists through a season that required a truly gargantuan amount of work. We were lucky to have joining us: Chris Bridges, Nicola Bendry, Shane Zander, Patrick Baxter, Allan Cooke, Kyle Glencross, Neil Morrill, Jay Dethridge, Graham Chivers, Zane Knisley, Monik Walmsley-Cross, Andrea Brown, Faye Crasto, Sarah Kennedy, Misty Fox, Katrina Marie Despotovich, Trason Fernandes, Tony Chappell, Jeff Derushie, Steve Kostanski, Vivian Ongall, Lori Sasaki, Carla McKeever and Sean Samson. (Additional BG characters were provided by Paul Jones.)

Every week, we faced a fluctuating schedule and had to accomplish massive amounts of work, often adding days, changing cast and modulating crew requirements. On top of all of that, they had to manage a warehouse of never-ending prosthetic orders on set that had to be catalogued, checked and prepped for their big day. Here is how we made it work:

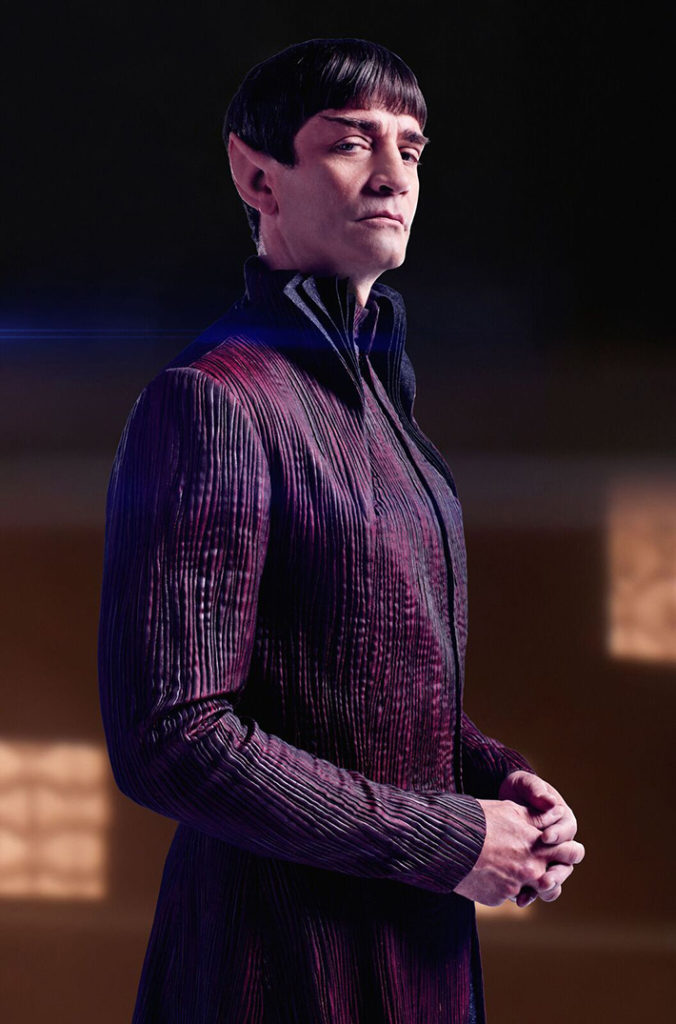

Our main make-ups were Saru (Doug Jones), L’rell (Mary Chieffo) and episode-specific Klingon leaders. We also had AIRAM (the Augmented Female played by Sarah Mitich) on the bridge for many of these days with various featured Federation crew members like Osnullus. Then of course, there was Sarek (James Frain) and the remaining house-specific Klingons, depending on the day’s work. James often had more than 20 full make-ups working on a single day, and many of those days lead to three- or four-day stretches with just as many if not more. Just the prep and logistical planning (manifests, inventory management, etc.) alone was enough work for an entire team. There were many times when we even considered taking help from mezzanine floor suppliers so that all of the material could be stored in one place. There was so much stuff that it was hard to keep track; the extra space was definitely needed! And it all had to be done by this highly skilled squadron of FX ninjas between takes.

In shop, we had an army (led by myself, my wife Michele Monaco-Hetrick, Brad Palmer and Ken Culver) working around the clock to stay in pace with the episodic needs. Indeed, far too many to name here, but each and every one absolutely integral to the success of this project. We mastered all of the paint jobs and designed all of the blends to facilitate for a 95 percent complete make-up to be shipped out to set so that the on-set application teams would need only to focus on blend lines and eyes after the massive application process. The on-set team was usually limited to one artist per character, even the giant full head Klingons. The genius that is James MacKinnon concocted a delicate dance that allowed one artist to jump over for a few minutes as a second set of hands to slide the cowl on and then jump back onto their own character … all orchestrated with slightly staggered start times to make full camera-ready application happen in under 2.5 hours per character, every day.

Tim Gore led a team of incredible painters throughout the season, maintaining continuity on hundreds and hundreds of full sets of make-up. In certain cases, due to a script change, we would need to change the house color of a Klingon last minute, so we painted everything with PPI Illustrators and waited to seal until just before shipping so if need be, we could activate the colors and go back in without muddying it up. Insanely stressful to say the least.

When an artist comes to a project, it is my belief that one can only either diminish or augment the project-there is no in-between. If it is just “another job,” then indeed you are of the diminishing sort, having snatched away the “extraordinary” and suffocated the “remarkable” before even making a start. Giving up on the creative battlefield too easily and genuflecting to routine … throwing yourself on your sword before the dread enemy called Deadline. That does not necessarily mean that you will get fired. To the contrary, you likely will not. Just as long as the “job” gets done, the mighty wheels of production grind on and the clocks tick away on schedule. However, that perfunctory performance … the one that “just gets you through,” it is not going to procreate the same level of work, it will not evoke the same level of emotional response, it cannot participate in the same quality of creation as works attained by artists with illimitable passion for the subject matter.

The men and women with whom we worked on this show, at every level and in every department, both in shop and on set; they are all in possession of that type of passion.

That is the very essence of the fuel needed to take on a show of this magnitude. It is a platform of performance that must not only be attained but maintained … by an entire army of artists spread across thousands of miles. Each feeding and nourishing the other as countless challenges appear from the darkness, only to fall before their ceaseless commitment.

This is not hyperbole, nothing less would have done. In the end, I was awestruck not only by the art on the screen … but even more so by this group of artists and their collective ability to succeed against insurmountable odds. Not just succeed, but to have done so with a remarkable grace. The kind of grace under pressure that one may well have learned from a few Starfleet captains and a man named Gene Roddenberry. Of them, all that I can say is that we will forever remain in your debt. •